15 Shades of Gray

Charles Gray’s Blofeld is a divisive figure to say the least. But whether you love him or loathe him, there’s one thing we can all agree on: he is shady. Here I unpick Ernst’s most waspish comments to reveal the uncomfortable truths about both him and the man he cannot live without - James Bond.

Opinions aren’t forever

In a recent Twitter poll, I asked followers what they thought about Gray’s Blofeld. To my surprise, the majority (70%) of Licence To Queer followers were in favour. Why suprised? Well, many of the most well known Bond websites and podcasts have little but vitriol for Gray’s Blofeld. Mind you, this usually goes hand-in-hand with a disdain for Diamonds Are Forever as a whole, something I’m on a mission to rectify.

Diamonds appears to have fallen down the fan rankings only relatively recently. David Stephens recently unearthed copies of the first ever issues of the James Bond Fan Club magazine, from 1979. In their first issue they named Diamonds Are Forever the best of the ten Bond movies released up to that point. In their second issue, they reported the results of a poll they had ran with members and it slipped to fourth place, but it was still ahead of films generally better regarded nowadays such as On Her Majesty’s Secret Service and From Russia With Love.

My own warm feelings towards Diamonds Are Forever are well known. When I started this website it was the subject of the first long-form piece I wrote. And since then, I have gone on to write in depth about Wint and Kidd, wax lyrical about the theme song and appear on podcasts proselytising for a reassessment of the film. But until now, I have not taken a long hard appreciative look through my queer lenses at the figure who is arguably responsible, more than anyone, for the film’s love/hate Marmite quality: Blofeld, as played by Charles Gray.

Something queer this way comes

The common negative criticisms of Gray’s Blofeld can be summarised as follows

He’s camp/laughable/too charming

He’s not physically threatening/a threat to Bond

He’s a big contrast from previous Blofelds, especially Telly Savalas

He’s hard to label in terms sexuality and gender identity

Among the few who sit on the fence, the consensus is that he’s the right fit for the film he is in. Several question why the villain even needs to be Blofeld - it would be better if Gray wasn’t saddled with the baggage of what had come before.

Now, I’m not saying I think all of those reasons are wrong. Most of them I agree with. But it’s because of those reasons that I love the character. And although I’m more than happy to have the strength of my own convictions, sometimes it’s nice to have backup.

Actor and host of the Tres Bond podcast Brandon McClelland said he loves Charles Gray’s incarnation of Blofeld because “he is decadence personified”. Robert Redfern credits him with being the best thing about Diamonds Are Forever: “My favourite Blofeld. Seriously, the utter disdain and high wit of his delivery as Ernst is an absolute joy.” ‘Gary K’ praises his “wonderful camp humour” which recalls the ’60s Adam West ‘Batman’ series.

It’s tempting to see Gray’s Blofeld as being particularly resonant with queer fans or those who appreciate elements of queer culture, but it’s not as black or white as that. There are several queer fans, including longtime Licence To Queerers Lotte and Fenna Geelhoed, who find Blofeld doesn’t work for them.

And yet… the data is definitely skewed in a queer direction. Or at least the direction of gay men.

In a 2020 video, Calvin Dyson controversially (for some) placed Gray’s Blofeld ahead of most of the others, being a runner-up only to You Only Live Twice’s Donald Pleasance and the facially-obscured feline-obsessed figure voiced by Anthony Dawson. More recently, another gay man, Tony Finnegan told me finds Blofeld to be “gayer than Right Said Fred dancing on a doily” and loves every minute of the “vicious old queen”. Gay fan ‘Roxie’, counts Diamonds Are Forever as one of his favorites, although he is glad the character was not reused: “I really enjoy Gray as Blofeld. I am glad his Blofeld’s confined to DAF and not in multiple films though. DAF stands out because of it.” For Jack Bell, Gray brings a lot of himself to the role: “Gray's haughty and campy ultra-Britishness feels so much of his own as compared to Pleasance's weird and hideous comic book arch-villain, and Savalas' joyful and snide tough-guy thug”.

Throwing shade

Whether you’re queer or not, one’s tolerance for Gray’s Blofeld does seem to hinge on one’s tolerance for ‘shade’.

Shade in the sense I’m using it here means “to express contempt or disrespect for someone publicly, especially by subtle or indirect insults or criticisms”. That’s how the folks at Merriam-Webster define it anyway. This sense of ‘shade’ was added to their dictionary in 2017, with its first recorded usage being taken from the seminal 1990 documentary Paris Is Burning. Burning fascinatingly explores drag culture in New York City, predominantly among its Latino and African American gay and transgender communities. The dictionary makers credited the TV show Ru Paul’s Drag Race with bringing the term into the mainstream over the previous decade. Like most drag slang, much of which has become mainstream today, it was first spoken by African American women.

It’s a terrifically evocative word, suggesting the casting of a shadow over another you wish to denigrate. It’s usually used as a phrasal verb with ‘throwing’. E.g. Blofeld was throwing shade at Bond in that scene.

And boy does Blofeld throw some shade.

I’m going to explore Blofeld’s portrayal of Gray using as the jumping off points 15 of his most shady remarks. Choosing just 15 was not an easy task. Almost every one of his lines is an acid-dipped barb, aimed in the direction of another character, place or institution. So that you can follow the character through the film’s story, I’ve kept them in chronological order.

1. “Making mud pies 007?”

By infantilising Bond, Gray’s Blofeld immediately announces himself as ‘different’. And yet he is, ostensibly, the same character as that depicted in four previous Bond films prior to Diamonds Are Forever. He certainly seems to recognise Bond, although he singularly failed to do so when Bond himself changed his appearance (to George Lazenby) in the previous adventure, despite meeting face-to-face for an extended period. Each to their own but, in all honesty, I find continuity matters such as these tiresome. The simple fact is: the filmmakers cast a different actor and decided to go in a different direction. Let’s move on shall we?

What I do find interesting is the very conscious desire to not repeat what had come before. Discontinuity was the aim all along. And although I will keep referring to Gray’s Blofeld, the man we have to thank/curse (depending on your preference) for the Blofeld we got in Diamonds is have Tom Mankiewicz.

Filmmaker and historian Steve Rubin asserts that Blofeld’s mannerisms and dialogue are “pure Mankiewicz”. So what did the writer think of his finished article? Certainly, Mankiewicz knew what he was getting into with Gray as he had worked with him in a stage musical, Expresso Bongo, in 1958. But according to the James Bond International Fan Club, in an interview later in his career, Mankiewicz “hinted at his disappointment at the version [of Blofeld] that ended up in the final cut”. It is, however, possible to interpret his comments differently. Mankiewicz actually said:

‘I saw Blofeld as such an elegant fellow, and they’d had two different Blofelds already. Charles Gray is the least physically pre-possessing Blofeld. Donald Pleasence had a big scar; Telly Savalas is certainly a menacing presence. And Charlie Gray, sort of flitting around in that penthouse, was more like Louella Parsons than Blofeld.’

It’s not certain whether Mankiewicz intended to be disparaging by comparing the character he wrote with an infamous 1930s gossip columnist. Certainly, his and Gray’s Blofeld never misses an opportunity to utter a waspish remark. But this is what makes him so memorable, mud pies and all.

2. “Howdy, son, we’ve been expecting ya. You got any personal business to take care of in there, you go right ahead.”

After his ‘death’ in the pre-titles sequence, Blofeld vanishes for more than half of the film. When he returns, he’s revealed to be living another man’s life: specifically the life of a Howard Hughes-type reclusive billionaire businessman.

The unnerving duality of the Blofeld/Whyte character is at the heart of Diamonds Are Forever. Ideas were not exactly forthcoming in the early stages of film production: the suggestion of having the villain be Goldfinger’s brother was, blessedly, shut down fairly quickly. Things were given a shot in the arm when Cubby Broccoli had a dream featuring his close friend, Howard Hughes. In the dream (which is related by Dana Broccoli on the Inside Diamonds Are Forever documentary), he saw Hughes through a window but, when Hughes turned around to look at him, it wasn’t Hughes; another man who had taken his place.

Despite the Hughes character being called Willard Whyte in the film he has a similarly alliterative name, a reclusive nature and a shared propensity to complete some of his most intense work from the comfort of his lavatory. Hughes must have seen the funny side because he gave all the help he could to the production of Diamonds Are Forever and merely requested a print of the film as recompense.

Blofeld relishes the opportunity to inhibit another man’s life, switching personae with apparent ease, affecting his vocal mannerisms to a tee. While it’s revealed a machine takes care of the accent, Blofeld must make the effort to use the Texas dialect - except, it doesn’t really appear to take any effort. Physically imposing he may not be, but it comes as something of a shock that he’s been pulling the strings, without taxing himself too much, all along. This harks back to the Anthony Dawson-voiced Blofelds in From Russia With Love and Thunderball where vocalisms are everything. I have a tendency to prefer the more loquacious villains, including those who are similarly maligned - Elliot Carver is another of my favourites for instance. Gray could have been presented as a physically imposing Blofeld - he was exactly the same height as Connery in real life. But it was a conscious choice not to accentuate his physical attributes. In Diamonds Are Forever, it’s Blofeld’s mastery over language that makes him a threat.

3. “Such a pity. All that time and expense, simply to provide you with one mock-heroic moment.”

Blofeld takes every opportunity he can to take a swipe at anything that might be considered conventional, such as heroism. Heroic derring-do of the Bond variety is, by extension, masculine and heteronormative. In most cultures throughout history it’s been the men who go off to war, splintering the nuclear family. The women stay at home to looking after the kids and pine for their husbands to return.

Blofeld is deeply unimpressed at Bond’s extinguishing the first of his visually-indentical doppelgangers (from the pre-titles) by sliding them into molten mud. He witheringly assesses it as a pathetic action of someone desperate to prove something. Blofeld was attacking toxic masculinity before it was ‘a thing’ - and by extension, macho violence.

Would such lines work anywhere near as well if spoken by an actor who didn’t carry such a frisson of ‘otherness’ himself?

Gray was gay, according to those who knew him best. We should always be sensitive to outing someone who never identified as such in their lives, but it was an open secret which his friends took for granted when they wrote about him in their own autobiographies.

Queer - and specifically gay - connections keep cropping up throughout Gray’s career.

Born into a middle class family, Donald Gray didn’t get into acting until his mid-twenties. Upon becoming a professional, he had to adopt a stage name - Charles - because there was already an actor with his real name. This is not unusual for actors, of course, but duality is baked into his career from the beginning.

By his late twenties, he was playing leading roles on stage, including Achilles in a production of Shakespeare’s Troilus and Cressida. Although Shakespeare doesn’t make a big deal of Achilles’ homosexuality in the text, it’s interesting that Gray was cast. He also ‘created a stir’ in a production of Love’s Labour Lost which had been designed by gay photographer Cecil Beaton (who was not only a favourite of the royal family but also Ian Fleming).

Aside from playing Blofeld, the role which he is known most for is as the Narrator in Rocky Horror Picture Show, a film which epitomises the queer experience for many.

Towards the end of his career, he appeared as Mycroft Holmes on film and in the TV series starring Jeremy Brett as Sherlock, another gay man.

When he died in 2000, many of Gray’s obituaries ended with the standard euphemism for a gay man: “He never married”. The obituaries of writer Tom Mankiewicz, who died in 2010, came to a close in the exact same way. Are two gay men responsible for one of the most memorable characters in Bond history?

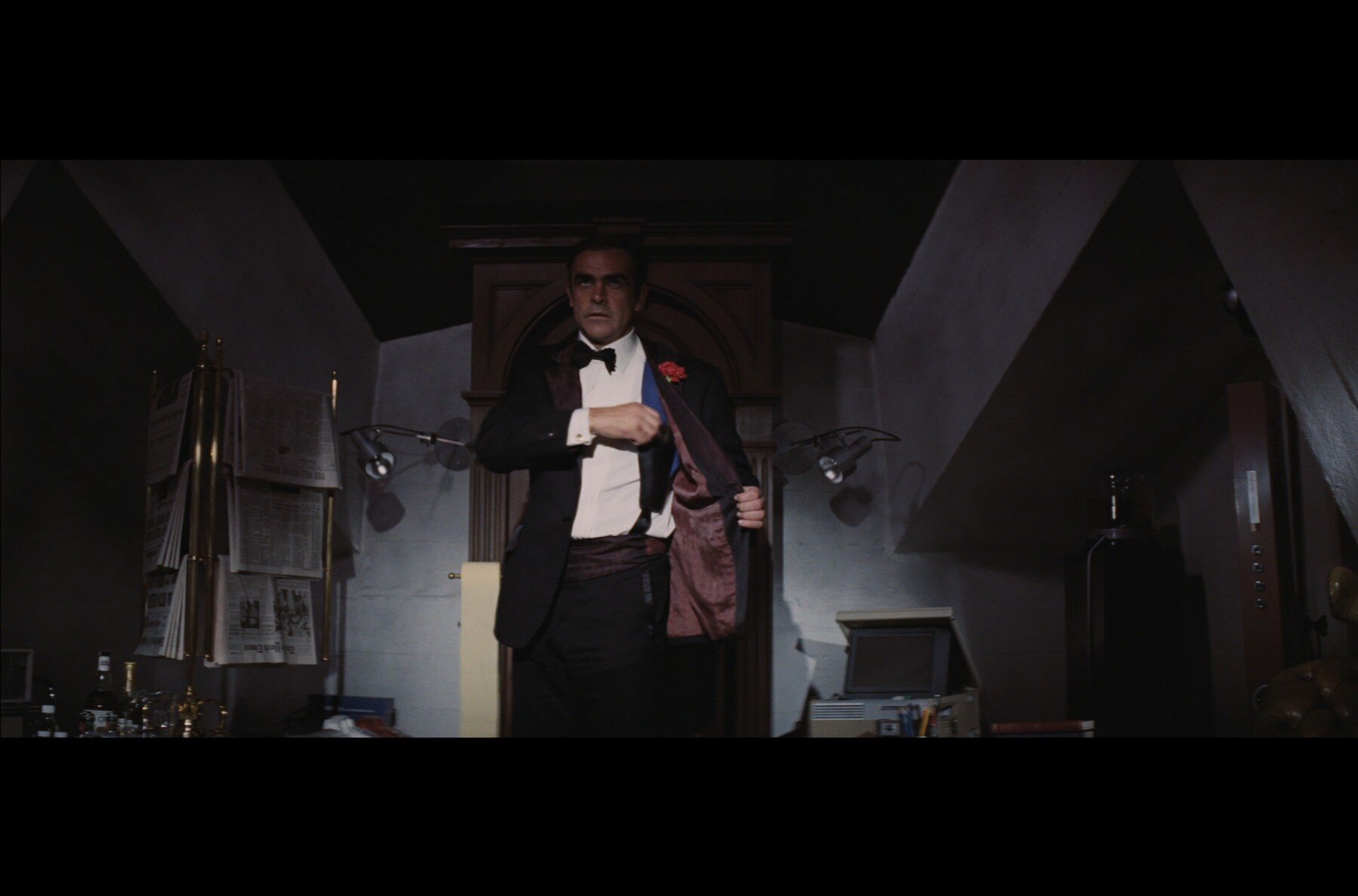

4. [While Bond manhandles a very pointy model of a missile] “Nice to see you haven’t lost that fine mental edge, 007.”

In a line written by Mankiewicz and delivered caustically by Gray, Blofeld gives his clearest indication yet that what he values above all else is mental prowess over physical specimens, no matter how visually appealing. See also: “Such fine cheeks…” (below).

5. “I do so enjoy our little visits, Mr Bond, however potentially painful they may be. But I’m afraid this one has come to an end.”

What would Blofeld be without Bond? It’s an intriguing notion. One suspects he would mostly be bored. Certainly there would be little in the way of conflict in his life.

There are many similarities between Gray’s Blofeld and the various iterations of the Joker in Batman media over the last eighty years, particularly the one played by Heath Ledger in 2008’s The Dark Knight. Like that character, he’s a motiveless malignity in the vein of Shakespeare’s Iago (from Othello), whose aims are always opaque - or multitudinous. This is a trait of previous Blofelds too, including Donald Pleasance (who wants to be paid by an unknown power for starting World War Three?) and the Telly Savalas edition (he wants recognition of his title and a pardon?!). Gray’s Blofeld is aiming to sell nuclear supremacy to the highest bidder, but this motivation is nonchalantly announced (it’s reported to Bond secondhand, through Willard Whyte) and quickly forgotten. Like Ledger’s Joker, he seems more interested in just watching the world burn - while making 007 watch.

Like Ledger’s Joker, Gray’s Blofeld also dresses in drag. But we’re getting ahead of ourselves...

6. “If I were to break the news to anyone it would be to you first, Mr Bond. You know that. But it’s late, I’m tired and there’s so much left to do. Good night, Mr Bond.”

Blofeld’s acknowledgment that he’s tired, with a busy agenda looming ahead of him the next day, humanises him. He, like us, gets exhausted to the point he is struggling to function. Bond, by comparison, is indefatigable. But it’s not as if Blofeld isn’t going to keep trying to wear him down.

Gray’s Blofeld plays with Bond like a cat with a mouse, holding off killing him until he tires of him. Rather than shoot him in Whyte’s penthouse, he maneuvers him into the lift with a curt but friendly “good night” and delivers him into the hands of Wint and Kidd. Their method of execution is about as baroque as it can get: burying Bond alive in a pipeline. It’s almost as if he wants Bond to escape and he’ll be disappointed if he doesn’t.

Like matters of continuity, debates around logic in a Bond movie largely bore me. And without Bond’s nasty habit of surviving (to quote a later villain), the films would be very unexciting - not to mention short. Both Mankiewicz and director Guy Hamilton delighted in inventing as many seemingly inescapable death traps as they could for 007. Diamonds is arguably the apotheosis of this, although Blofeld’s final attempt to dispose of Bond is the most prosaically escapable (and very similar to that in OHMSS): even on the brink of his plan coming to fruition and after Bond has become “tiresome”, he refuses to kill Bond and merely has him locked up in the brig. He simply cannot ‘be’ himself without James Bond in his life.

7. “Well go on, go on, it’s merely a lift. Or perhaps I should say “elevator”. In any event, I’m sure you’ll find it much more convenient than mountaineering about outside the Whyte House.”

Why resort to using your fists when your words are even more pointed? Rather than force Bond into his next potential death-trap, Blofeld talks him into it. The gun is just there for insurance purposes. Blofeld baits Bond by once again lampooning his heroic physicality. One cannot imagine Gray’s Blofeld has ever done much in the way of mountaineering (even if a later Blofeld embodiment, Spectre’s Franz Oberhauser, is apparently partial to rock-climbing).

8. “Well, Well. Look what the cat dragged in. I’m delighted to meet you Miss Case. I had so dreaded the prospect of making this tedious journey, alone.”

And so we come to it: the much hated/celebrated (again, depending on your point of view) scene where Blofeld drags up. Or does he?

Drag is funny to some and scary to others. Both reactions have the same root cause: drag is a subversive art form which destabilises binary ideas of gender. Drag shows us, as academics like Judith Butler have argued, that gender is a performance. It’s a view I subscribe to completely and you can either laugh about this, valuing the endless diversity of the human experience, or get angry about it (but, y’know… life’s too short and all that).

Purely from a plot point of view, it has always made perfect sense to me why Blofeld puts on some ‘female’ apparel. His not-very-convincing disguise serves to keep the plot moving, giving a reason for Tiffany to be drawn away from the protective, avuncular figure of Q. She’s not sure if she’s seen Blofeld or not and by the time she realises her hunch was right it’s too late.

By the standards of Paris Is Burning, Blofeld is not the world’s best drag queen. He will not be winning Ru Paul’s Drag Race anytime soon. But that’s the whole point: he’s not trying to either ‘pass’ as a woman or look great. He merely wants to be seen and recognised by one individual who has, in some capacity, probably through several intermediaries, been in his employ.

Does Blofeld’s effort even count as drag? Most successful drag queens seek to exaggerate, not imitate, women. Blofeld is wearing a blue trouser suit. It’s really only the hair and makeup which are exaggerations of conventionally female traits. Even so, some viewers find the scene uncomfortable, which was surely the intention all along.

Category is… megalomaniac realness?

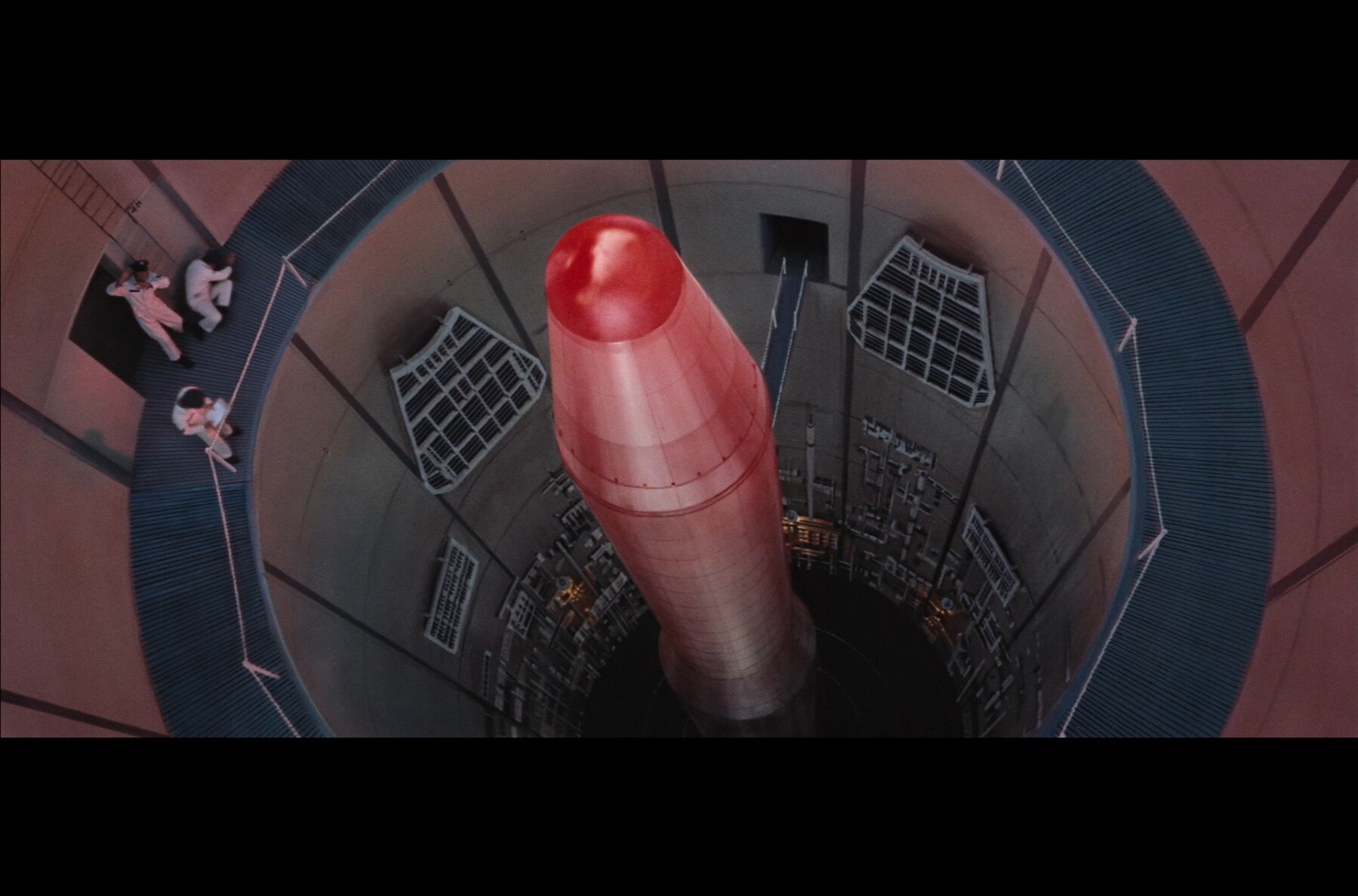

9. “Calm yourself Metz. This farcical show of force was only to be expected. The great powers flexing their military muscles like so many impotent beach boys.”

Blofeld has little time for the penis-measuring competition of the Cold War.

The end goal of Gray’s Blofeld is, superficially at least, similar to that of Pleasance’s. In You Only Live Twice, Blofeld is playing the powers off one another to start an apocalyptic war to leave another nation the victor (and get paid in the process). In Diamonds Are Forever, Blofeld is more surgical, targeting the weapons’ capabilities of the USA (missile silo), Russia (submarine) and China (rocket base) in turn to show off the power of his diamond-powered laser, which he will then sell to the highest of these three bidders, thus leaving one of them all-powerful.

But Gray’s Blofeld goes one step further. He’s not merely aiming to turn a profit; he wants the pleasure of seeing the world’s powers brought to their knees. In perhaps his most shady critique of all, he succinctly paints a picture of them as “beach boys”, so obsessed with appearances and so overloaded with steroids that they cannot perform sexually - which surely is mostly the point of spending all that gym in the first place.

He doesn’t speak from a place of jealousy: sex seems to hold little, or no, interest for Blofeld. Indeed: you could even see him as attempting to shatter the very institutions which, through the whole of human history, have kept mostly straight men at the top of the pecking order. As Meg-John Barker pithily observes: “Capitalism is the real monster”. Capitalism relies on traditional gender and sexuality norms being rigorously policed: at its crudest, it requires women to stay at home to look after the kids. And queer sexuality destabilises the family unit.

Even though Blofeld is shown attacking China and Russia, countries which were following unequivocally anti-Capitalist ideologies in 1971, in the daily-lived reality in those countries, women and minorities occupied roughly comparable status to their equivalents in the West.

I’m not arguing that Blofeld’s real aim is to instil anarchy (in the literal sense of there being no controlling authority). If his plan had worked and he was a man of his word, he might have subjected the world to even greater tyranny under one omnipotent nation state. But one suspects he wouldn’t be prepared to cede control of his diamond laser. If you were in his position, would you?

10. “How disappointing. I was expecting one head of state at the very least. Surely you haven’t come to negotiate Mr Bond? Your pitiful little island hasn’t even been threatened.”

Blofeld hits Bond where it hurts: in his national pride. The reality was that, well before 1971, Britain was not a world power to compete with the three that Blofeld targets with his jewellery-powered satellite. Fleming knew this and this is one of the main reasons the books sold so well - they restored British national pride, albeit in the form of fictionalised fantasy. But Blofeld’s shade remark is one of the most explicit articulations of the idea in the Bond films, echoes of which can be found through many of the films that follow, especially GoldenEye (“For England, James?”) and Skyfall (“Chasing spies, so old fashioned. England. The Empire. MI6.”)

11. “I do so hate martial music.”

As we have seen already, military might bores Blofeld. Even the aural version brings him no pleasure.

12. “As La Rochefoucault observed: humility is the worst form of conceit. I do hold the winning hand.”

One could argue that having Blofeld quote a Seventeenth Century nobleman makes him snootier than Bond. But Bond is no stranger to pontification himself, having lectured M about sherry vintages earlier in Diamonds Are Forever. Bond and Blofeld both enjoy being know-it-alls.

As it turns out, although Francois Duc De La Rochefoucauld was famous for his aphoristic sayings, ‘humility is the worst form of conceit’ was not one of them. The closest he gets, in his book of 504 Maxims (published in 1678), is number 254:

Humility is often a feigned submission which we employ to supplant others. It is one of the devices of Pride to lower us to raise us; and truly pride transforms itself in a thousand ways, and is never so well disguised and more able to deceive than when it hides itself under the form of humility.

Not quite as punchy is it? It’s clear to see why Mankiewicz paraphrased it in the screenplay.

Later in the same book, La Rochefoucauld draws out the distinction between feigned and true humility:

Humility is the true proof of Christian virtues; without it we retain all our faults, and they are only covered by pride to hide them from others, and often from ourselves.

False modesty is most unbecoming. Although Blofeld is magnanimous in victory, he is still proud of getting one over on 007.

13. “As you see, the satellite is at present over… Kansas. Well, if we destroy Kansas the world may not hear about it for years.”

By slagging off the US state with the reputation for being backward-thinking, with its endless plains of wheat and (to Blofeld’s mind) little else of note, the character is aligning himself with everything metropolitan.

It’s long been a trope of gay narratives for characters to ‘find themselves’ by moving from the rural places they grew up to the big city, where they can live their ‘truer’ authentic selves. It’s undoubtedly easier to be yourself if you’re around people like yourself - you can’t be what you can’t see. But the rural/urban reality is more complex for many. A 2012 study of French and American gay men found a more ambivalent relationship with urban spaces:

“While the city exists as a space of social practices where alternative sexualities can be experienced and explored, at the same time for many rural gay men the city remains substantially unattractive. In their view, the perceived “effeminizing power” of the city questions and challenges their attraction for this space.”

A handful of fictional narratives in recent years have portrayed queer characters living their true selves in the rural communities. For instance, the 2017 British film God’s Own Country which portrays a young farmer learning to love himself, others and the land on which he was raised. And social media has allowed queer people in rural areas to connect.

As far as Blofeld is concerned, he’s about as far from a farmer as one can get. Although, if he ever made it to Kansas, he might change his mind. Who knows: he may even make a friend of Dorothy.

14. “Tiffany my dear. We’re showing a bit more cheek than usual, aren’t we? What a pity. Such nice cheeks too. If only they were brains.”

When the Guardian obituary for Tom Mankiewicz noted the “tongue-in-cheek-seam” that ran through the writer’s work, it might have been a knowing nod to this classic line.

While it’s fun to speculate, we should be careful about using this line to read anything in to Blofeld’s sexuality. His orientation is intentionally hard to pin down or label in any version of the character. Most people (including Fleming in the novel of Thunderball) settle on somewhere in the asexual spectrum. But in Diamonds, I’d go for sapiosexual: he’s someone who finds intelligence attractive above all else. It’s pretty clear here that he loses respect for Tiffany as soon as she’s shown herself to be less efficaciously cunning. While she’s positioned as a classic damsel in skimpy clothing, Blofeld has already made it clear in an earlier scene that he considers her charms to be little more than an irritation: “I’d put something on over that bikini first, my dear. I’ve come too far to have the aim of my crew affected by the sight of a pretty body.”

Bodies hold no appeal for Gray’s Blofeld, only minds.

15. “Disengage! Lower! Not up!”

We feel Blofeld’s frustration in the bathotub. It’s an intentionally ignominious end for the character. What could be more disastrous for a man so steeped in class, so used to owning any room he is in, no matter how expansive (thanks Ken Adam), than being crammed into a receptacle barely big enough to contain him.

It all seems like it’s going to plan…

Whenever I watch Blofeld fitting himself inside the bathosub I can almost hear him quoting under his breath Shakespeare’s Hamlet: “I could be bounded in a nutshell and count myself a king of infinite space, were it not that I have bad dreams.” Even so self-contained, he’s still the king of the space - and he knows he will return! Blofeld is unrepentantly looking out for himself, right up until the final moments - and he definitely won’t have bad dreams about it later on.

But it quickly dawns on him that something is amiss. After being uncermeoniously plopped into the sea, he is swung around like a child’s play thing. Bond has graduated from making mud pies to toying with his nemesis.

His exhortations to Bond, who he presumes to be the crane operator, become increasingly irate. They are surely familiar to anyone who has ever been let down by another singularly failing to complete a simple task.

There’s a bit of Blofeld in all of us. Some of us have more than others.