No Time To Dirk: Bond and Bogarde

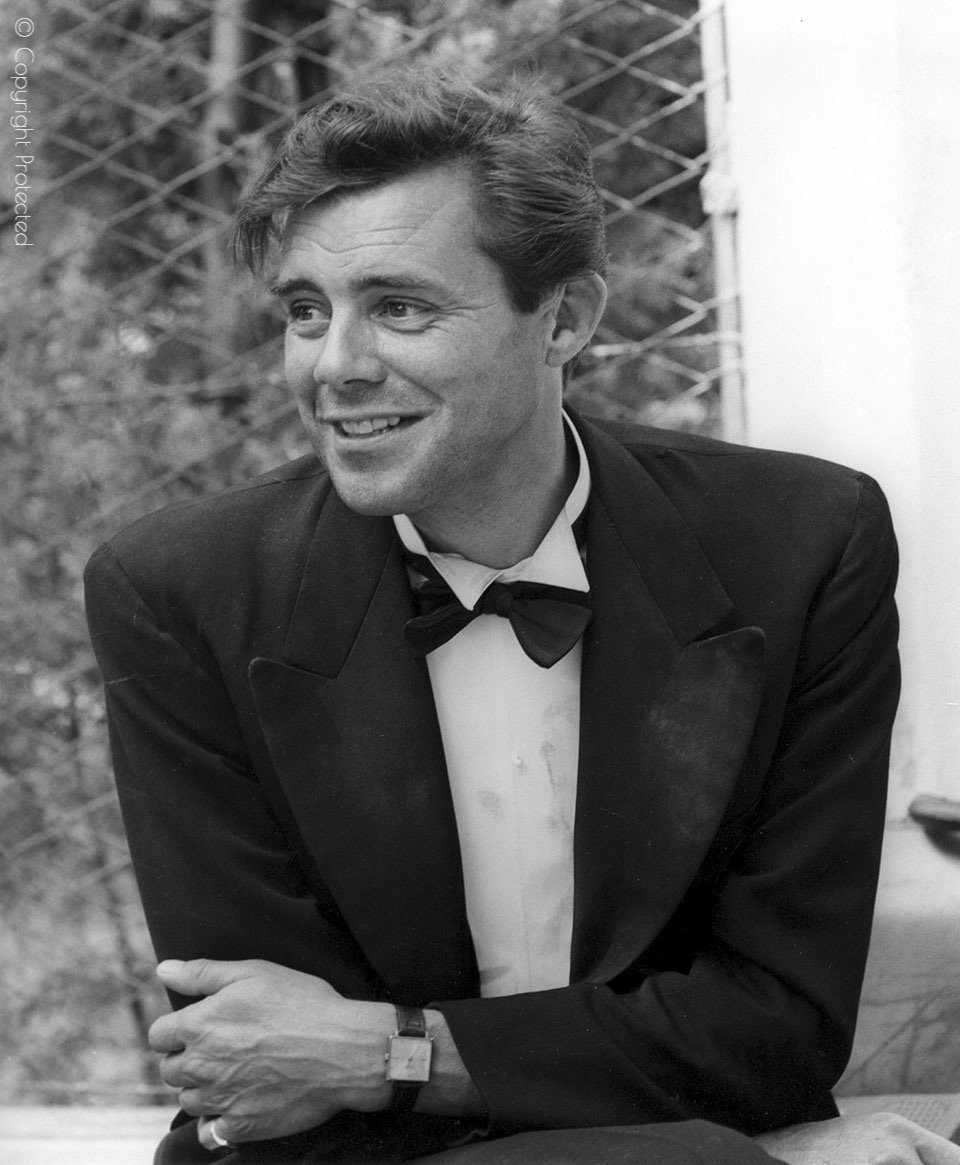

60 years ago, when the movie Bond began, England’s most popular actor was Dirk Bogarde, a closeted gay man. Dirk was even approached to play Bond. But big Bogarde fan Callum McKelvie is glad the matinee idol never donned 007’s tux (although he would have looked great in it).

With No Time to Die not only ending Daniel Craig’s tenure as James Bond, but literally enveloping him in a ball of flame, the door is wide open as to where the character could go next. Barbara Broccoli’s recent comments that Bond 26 would be a ‘reinvention’, caused some controversy. Now speculation abounds as to the character’s future and who will be the actor to take him there.

In a September 2021 Interview with Attitude Magazine, Ben Whishaw, when asked if he would love to see an out gay British actor in the role, stated: “God can you imagine? I mean, it would be quite an extraordinary thing. Of course I would love to see that.” Yet with all this speculation surrounding the next James Bond, the 60th anniversary has had me personally thinking about those actors who narrowly missed out on the role. From James Brolin to Sam Neill, the list of ‘nearly’ Bonds is expansive. Back in 1959 however, when Kevin McClory and Ian Fleming were involved in the original unmade version of Thunderball, on the long list of potential actors considered for the role was one which intrigues me more than all the others. A man who was at that point the most popular film star in England, not to mention a closeted gay man and my favourite actor - Dirk Bogarde. But just who was this pretender who nearly stole Sir Sean’s crown?

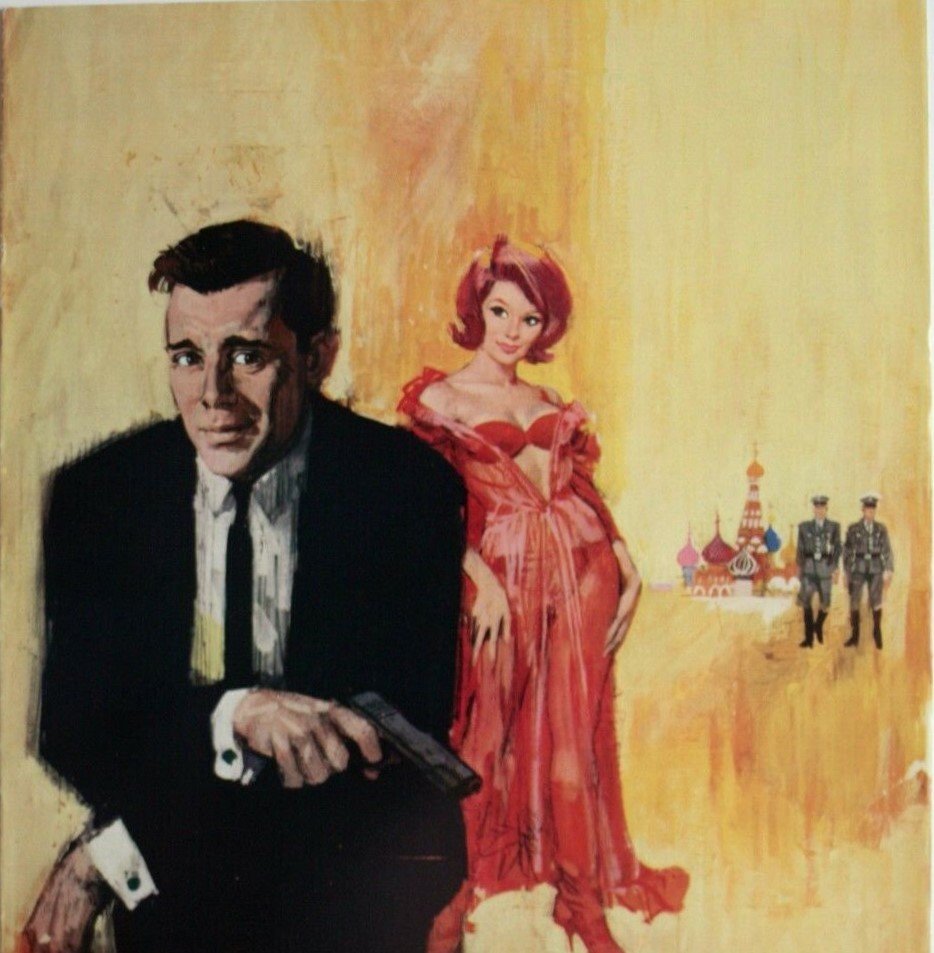

Poster art for spy spoof, Hot Enough for June

Most likely the teenage crush of your grandma, Dirk Bogarde was a British actor and author who was born on the 28th March 1921. Originally known for playing delinquents in films such as The Blue Lamp (1950), it was the 1954 comedy, Doctor in the House, that saw him become a matinee idol. For the rest of the decade he worked for the Rank film company largely in comedies and melodramas. During the 1960s he purposefully sought more challenging roles including a number of films with Joseph Losey, such as the 1963 masterpiece (and my favourite film of all time) The Servant, the brutal war drama King & Country (1964) and the chilling Accident (1967). Although he still took roles in commercial films, Bogarde continued to challenge himself, playing the lead in Luchino Visconti’s highly regarded Death in Venice (1971). He largely retired from acting in 1978 and instead began a second career as a writer. He passed away in 1999 at the age of 76.

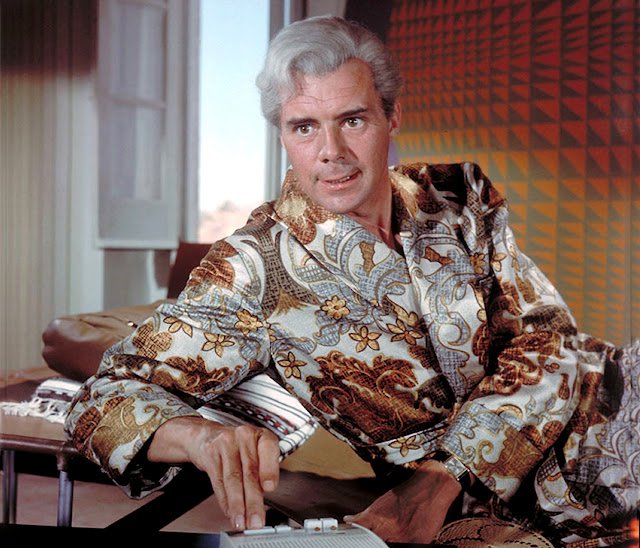

Dirk Bogarde as the flamboyant arch-villain Gabriel in 1966’s Modesty Blaise

Except that doesn’t quite put across the sheer magnetism of the man. There’s something about Bogarde that attracts people towards him, creating a cult of dedicated fans. Recently when I picked up a biography second hand in a charity shop I found it stuffed full of clippings and notes going back decades. So just what is his appeal? I caught the ‘Bogarde bug’ relatively recently during the early stages of the Covid-19 Pandemic. My Bond love had previously fostered in me a taste for the Eurospy films of the 1960s and it was for this reason that I found myself one Friday night taking in the delights of 1966’s Modesty Blaise with a bottle of Lidl’s finest Beaujolais. Certainly the most outlandish of Bogarde’s small selection of spy films, Modesty Blaise is probably best compared to pop-art 60s counter-cultural works such as Barbarella and Danger Diabolik (both 1968). This zany comedy sees Bogarde cast as arch criminal mastermind Gabriel against Monica Vitti’s titular female super-thief. Wearing a bleach blonde wig and constantly talking about ‘mother’, Gabriel is certainly a queer coded character. Bogarde’s performance is so over the top and deliciously camp that it immediately made the film something of a go-to comfort watch for myself. Looking into the film more, I found myself increasingly drawn to the actor behind the character. I hungrily devoured any information I could find - documentaries, biographies, collected letters. Very soon I became infatuated.

There’s a level of control to Bogarde's performances. Every movement seems precise. Every blink of the eye or wave of the hand is considered and choreographed. There’s an underlying intensity which is intoxicating. Then there’s the man himself. At best immensely charming with a visible passion for his art. At worst aloof, with an acid tongue and a veritable spikiness which he would unleash with barely concealed ferocity on the unsuspecting interviewer. I certainly have my moments of ‘spikiness’. My own anxieties and fears sometimes cause me to lash out. I’m fully aware that to my friends I can often present as an open book, freely discussing my innermost feelings but slamming the pages shut if I feel exposed or the slightest bit vulnerable. If anyone makes a comment on my personal life that I disagree with, I find myself getting red in the face and making short, sharp remarks. Admittedly, particularly when I was in my teenage years, much of this came from my own insecurities regarding my sexuality, my desire to be open and proud, conflicting with my own fears as to how this could result in me being victimised and harassed.

Image: Dirk Bogarde with his manager and partner of forty years, Anthony Forwood

Was this something Bogarde felt? It’s not a subject it’s entirely fair to speculate on. Bogarde’s sexuality was often a topic for debate within the gutter press, but he chose to remain closeted. It seems most likely that Bogarde was in a committed relationship with his manager Anthony ‘Tony’ Forwood for nearly forty years. In 1999 the BBC produced a two-part documentary entitled The Private Dirk Bogarde, in which many family members and friends spoke openly of the actor's sexuality. There are numerous upsetting stories and rumours regarding Bogarde’s own feelings towards the subject. According to John Coldstream’s excellent biography, there is “uncorroborated information - at second hand, but from a disinterested source” that from the late 1950s to the mid 1970s Bograde would once a year attend aversion therapy, which would involve him being shown erotic photographs of men and given pills which would force him to vomit. Coldstream points out that it’s worth remembering that homosexuality was officially listed as a mental illness in the United Kingdom until 1973. When I came out I was very fortunate that it was in the UK of 2012, a far more accepting world than the one the young Dirk Bogarde was forced to live in. Until 1967, homosexuality was completely illegal and could result in a prison sentence.

Nonetheless, whilst I would not be naive enough to compare my experience as a young gay man to his, I did find myself relating to this enigmatic figure. I saw in him a kindred spirit, someone whose ‘spiky’ nature sometimes got the better of him, seemingly when he felt his privacy was threatened. So imagine my delight when I read Robert Sellers' The Battle for Bond and came across the section where he states that in 1959, during pre-production on the original Thunderball film project, a new “fascinating name entered the frame, that of Dirk Bogarde.” According to Sellers, Bogarde was approached and, due to his popularity at the time would most likely have been committed to other projects - though he might have been interested. Bogarde as Bond… my little heart could barely contain its excitement.

Dirk Bogarde showing off his more action orientated side in 1965’s The High Bright Sun

Of course the most obvious question is would he have actually made a good James Bond? It’s difficult to know. Some Bond alumni didn’t think so. Director Lewis Gilbert, when reminiscing about his work with Bogarde in the 1962 high sea’s epic, Damn the Defiant, stated that Bogarde was no good at action and “he wouldn’t have made a good James Bond.” However, like many of those associated with Bond, Bogarde’s wartime career had seen him work in Military Intelligence and he certainly had the looks for the part. The closest the actor came was 1964’s Hot Enough for June. Ostensibly a spy comedy, it's actually a fairly neat little Cold War thriller with a great deal of tension woven throughout and nowhere near as silly as other 60s spoofs. He cuts a dashing figure and certainly looks great in a tux, though his may have been a darker and far more intense portrayal than Connery’s was.

But let’s take the idea of this ‘what if’ to its furthest possible conclusion. Let’s say that in the late 1950s Bogarde had been cast as Bond in the original Thunderball. A series of James Bond thrillers is launched and has the same level of success as the series we know and love today. Bogarde would of course have been contracted for multiple films and have become an even bigger international star. However, had this occurred it would have been around the time that Bogarde began to branch away from his image as a matinee idol and pursue more challenging and controversial material. One film in particular, 1961’s Victim, showed just how daring and brave an actor he could be. Produced when homosexual acts between men was still illegal, Victim was a heartfelt appeal for sympathy and leniency. Bogarde, by accepting the role of the closeted gay hero of the film, risked not only his career, but also his privacy and relationship with long-term partner Anthony Forwood.

Victim deals with the troubling topic of homosexual men being blackmailed due to the laws against them. Indeed, at the time the film was made, some 90% of all blackmailees were gay men. The film smartly tackles this subject by framing itself as a crime thriller. Bogarde stars as Melville Farr, a successful and married barrister who is soon to take silk. However a younger gay man, Barrett, with whom Farr had some form of relationship has become the target of a group of blackmailers. When the horror of a prison sentence drives Barrett to suicide, Farr decides to hunt down and expose the criminals responsible. A number of actors had already turned down the role of Farr, including James Mason and Jack Hawkins, with Bogarde’s casting requiring a de-aging of the original character. Bogarde himself made a key contribution when he personally rewrote an integral scene in which Farr confesses his feelings for Barrett to his wife, declaring: “I stopped seeing him, because I wanted him. Do you understand?! Because I wanted him!” It remains an incredibly powerful moment.

On its release, the film received some praise and, perhaps most importantly, invited discussion of its subject matter. A review in The Times noted that it invites “a compassionate consideration of this particular form of human bondage.” Despite initially being denied a US release, when it appeared in a handful of cinemas in 1962 the New York Times review stated it was “unprecedented and intellectually bold.” Clearly, Victim had generated thoughtful and considered attention. What were Bogarde's own views on the seminal film? In a letter dated April 1996, Bogarde would refer to Victim as “a very dull little film which I perked up with a good scene.” However, deep down there is a sense that he was extremely proud of Victim. In another earlier letter dated June 1985 he responded to a request by student Paddie Collyer enquiring about the impact of the film: “The letters which poured in from families, from men, from wives, were heartbreaking,” he explained at one point “but we had lifted the corner of a veil, and people suddenly realised that they were ‘not the only ones’ in the world.”

Dirk Bogarde and Sylvia Sims during the film’s key sequence

In 1967 the Sexual Offences Act partially decriminalised homosexuality. One of the key figures in getting the law passed was Arthur Gore*, the 8th Earl of Arran - though, according to The Socialist Worker, he did later comment that: “I ask those [homosexuals] to show their thanks by comporting themselves quietly and with dignity. Any form of ostentatious behaviour or public flaunting would be utterly distasteful.” In 1968 however, Arran would personally write to Bogarde explaining that he had just caught a screening of Victim on television and declaring his admiration for the actor's “courage in undertaking this difficult and potentially damaging part.” However the key comment of note is that Arran claims that change in the public’s opinion on reform (he states a change of 48% to 63%) in favour was “largely due to your two films, The Servant and Victiim.” True? That we’ll never know, but the film clearly made an impact.

Once again though, let's jump back into the multiverse. It’s 1959 and Dirk Bogarde has accepted the role of James Bond, the subsequent film is a huge success and a series based on the novels of Ian Fleming is launched. James Bond is here to stay. But if all this had occurred…what about Victim? Of course it would be churlish to a say that a single film was responsible for the partial legalisation of homosexuality in the United Kingdom and I don’t mean to suggest that for one moment. However it can be considered a small piece of a much larger whole. Had Bogarde donned the tux and Walther PPK, it’s unlikely he would have been available (even if he had been willing) to don the court robes of Melville Farr as well.

Image: ‘You Only Live Twice’ was released one short month before homosexuality was partially legalised in the England and Wales.

Right now, it is widely feared that, following its landmark overturning of the Roe vs Wade ruling on abortion, that the US Supreme Court will target gay marriage first and then sexual acts between men. Republican Senator Ted Cruz has stated that the Supreme Court was ‘clearly wrong’ to legalise gay marriage, adding weight to these concerns. Victim is a terrifying look into a past full of discrimination and fear. At points yes, it shows its age and some of its views on LGBTQ+ rights are certainly outdated - but the raw power of the film cannot be denied. There is a sequence where an elderly gay man remarks that: “I can’t help the way I am but the law says I’m a criminal. I’ve been to prison four times, I couldn’t go through that again” going on to state “I’ve made up my mind to be ‘sensible' as the prison doctor used to say. I don’t care how lonely, but sensible.” When I first saw the film I sobbed. How could the law have been so cruel? In many places, how can it still be so? During the release of the first five James Bond films, Dr No to You Only Live Twice, this was very much the case in the UK. Indeed it was only a short month after the latter that homosexuality was partially decriminalised (in England and Wales but not Scotland, which took until 1980). It would take decades for full legal equality to be realised.

I love Bond. It’s a huge part of my life. It has and continues to give me so much pleasure. But some films are more important than Bond. As LGBTQ+ persons continue to fight for our rights to love who we love and be who we are, I’m glad that fate made Bogarde forgo the role of the world’s greatest secret agent. Instead his greatest legacy will forever be, and should always be, Victim, a film which remains as important and poignant today as it was upon its release in 1961.

In the day, Callum McKelvie works for a history magazine. At night he writes short fiction (often with a horror theme and often queer focussed), eats and drinks too much and does his best to live the Bond life on a budget.

Callum and David discuss Dirk Bogarde as Bond on this episode of the Licence to Queer podcast. Also on YouTube.

Bibliography

Attitude (2021) ‘Ben Whishaw Would Love to see an Out Gay British Actor Cast as James Bond’ Attitude Magazine, 27th September 2021

BBC (1999) The Private Dirk Bogarde Arena, BBC Television

Coldstream, John (2004) Dirk Bogarde: The Authorised Biography Orion

Coldstream, John (2009) Ever Dirk: The Bogarde Letters Phoenix

Dirk Bogarde.co.uk (2022) ‘Discreet Reformer’

New York Times (1962) ‘Victim Arrives: Dirk Bogarde Stars in Drama of Black Mail’ New York Times

Pink News (2022) ‘Disgrace’ Ted Cruz says Supreme Court was ‘clearly wrong’ to legalise same-sex marriage’

Sheridan, Morley (1999) Bogarde: Rank Outsider Bloomsbury

Socialist Worker (2017) ‘A Beginning of the End for Shame’

Sellers, Robert (2007) The Battle for Bond Tomahawk Press

Times, The (1961) ‘Intelligent Film on Homosexuality’

*Further reading

Another Bond connection with Bogarde comes by way of Arthur Gore, Earl of Arran, discussed above. Gore was the cousin of Ian Fleming’s wife. His nickname was ‘Boofy’ which Fleming gives to gay-coded Mr Kidd in Diamonds Are Forever. You can read more here: https://www.licencetoqueer.com/blog/homos-make-the-worst-killers