Queer re-view: From Russia With Love

Seductive Russian agents used as honeytraps, British civil servants photographed in compromising positions, sex scandals... and that was just in the real world. On cinema screens, Bond was embarking on his second adventure, a story you could have ripped from the headlines. All in all, there was rather a lot going on in 1963.

If this is your first time reading a re-view on LicenceToQueer.com I recommend you read this first.

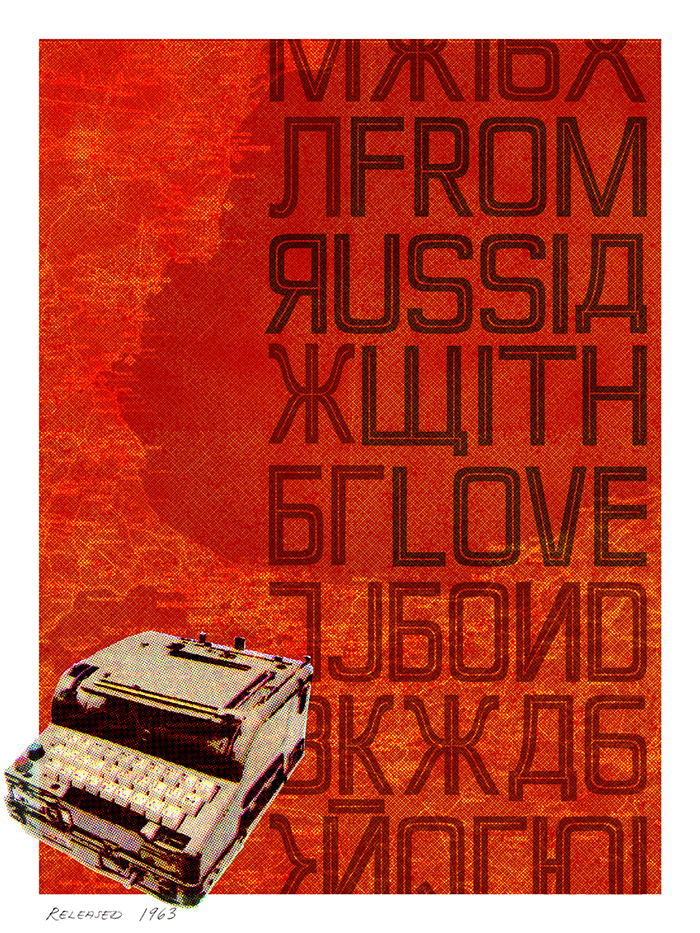

‘Inspired by From Russia With Love’ by Herring & Haggis

“The name’s Bond, Flaming Bond?”

A British civil servant falls in love with a beautiful Russian. The Russian turns out to be the bait in a trap. Later, it is revealed that, unbeknown to him, the British man was photographed having sex with the beautful Russian.

It’s not just the story of From Russia With Love but also that of the real-life John Vassall, who spied for the Soviet Union from 1954 until he was arrested in 1962, the year before From Russia With Love’s release. When he was arrested he confessed immediately, claiming to have acted under threat of blackmail from the KGB. He said he had been lured into a classic honeytrap by a seductive spy and then photographed in compromising positions.

So far, so similar to From Russia With Love, the plot of which hangs on honeytrap. Bond is tasked with bringing a decoding machine back to England, using his body to get it. Unlike Vassall, Bond knows he’s walking into a trap but he doesn’t know he will be photographed having sex with his Russian love interest.

The most significant difference between Vassall and Bond is that Vassall was gay. The Russian spy he fell for was another man, the name of whom Vassall did not reveal (possibly didn’t even know). Vassall referred to his man of mystery only as ‘The Skier’, which immediately brings to my mind Anya’s boyfriend at the beginning of The Spy Who Loved Me. So in essence, Vassall fell for an athletic action man; a Russian version of Bond.

Vassall said he was photographed having sex not with ‘The Skier’ but a whole bedful of young men, after being drugged. Although some doubt the veracity of Vassall’s account, citing financial recompense from the KGB rather than the threat of being outed as gay as the motive behind his betrayal, the reality was that blackmail of gay men was widespread in the Britain of the 1950s and 1960s.

This was so much of a concern that the Conservative government appointed Sir John Wolfenden to lead a committee which look into the legal status of homosexuality. After all, if homosexuality was not illegal, the KGB would not be able to blackmail gay men by threatening to expose them as criminals. When the 155 page report was published in 1957 it became a bestseller and opened up the public debate around homosexuality. And although the recommendations of the report were dismissed by the government who commissioned the report, it led to homosexuality being partially decriminalised in England ten years later.

I rarely undertake a comparison with the source novel in these queer film re-views, mostly because only a handful of them are translated so faithfully to the screen. But in the case of From Russia, With Love, the subtle differences between the novel and film, released only six years apart, reveal a lot about changing attitudes to sexuality in Britain at the time.

The novel of From Russia, With Love was released the same year of the Wolfenden Report. The Wolfenden commission was set up three years earlier, in 1954, so Fleming would have known about it while writing his novel. Did he intend to echo this real life event? In the novel, a restless Bond is assigned to a committee trying to work out how things went so disastrously wrong in the Burgess and Maclean case specifically. It’s a tempting parallel.

Burgess and Maclean were two of the three queer members of the Cambridge Five: five former university friends, who had become top civil servants, being publicly revealed as spies for the Soviet Union in 1951. The extent to which Burgess and Maclean were blackmailed because of their homosexuality is debatable. In Burgess’s case, his outspokenness about his gayness (especially after he’d had a few drinks) became more and more of a problem. But being discreetly homosexual was tolerated in the upper class circles in which he mingled. Some argue that the Russians may even have considered his being gay an advantage, allowing him access to the top echelons of influence.

But for most men it was considered a weakness, one which the Soviet Union could exploit. In the novel From Russia, With Love, the KGB’s chess-playing strategic maestro Kronsteen probes what he knows about James Bond, trying to work out the right way to destroy 007’s reputation:

“English spy. Great scandal desired. No Soviet involvement. Expert killer. Weakness for women (therefore not homosexual, thought Kronsteen). Drinks (but nothing is said about drugs). Unbribable (who knows? There is a price for every man).”

One can almost hear the cogs turning in Kronsteen’s mind: if only Bond had a weakness for men, not women, I could sort all this out quickly and get back to my chess game! He goes on to compare the present assignment with a previous job “On that occasion the matter was simple. The spy was also a pervert.”

It’s safe to assume that ‘pervert’ is thinly-veiled code for homosexual.

Although Fleming claimed at the start of the book that “a great deal of the background to this story is accurate”, it’s something of an exaggeration. Nevertheless, by referring to real-life cases of queers being exploited by the Soviets, he brings a greater verisimilitude to his novel. And as far as the British government was concerned, this was a very real problem.

The committee that Bond joins is led by Paymaster Troop, a character Bond dislikes intensely because he’s so stuck in the past. Compared with Bond, Troop seems positively bohemian. When Bond suggests they need move on from the tried and tested (but now failing) Second World War approaches to spying, Troop rejects Bond’s idea of employing intellectuals, calling them “long-haired perverts”. That word again. Except this time, it’s made explicitly clear, with Troop elaborating: “I thought we were all agreed that homosexuals were about the worst security risk there is”. Bond insists Troop has the wrong end of the stick (“All intellectuals aren’t homosexual. And many of them are bald.”) but doesn’t feel compelled to stick up for homosexuals.

Troop conflates homosexuality with disloyalty to queen and country. He would have jumped at the chance to include the case of John Vassall in his report. And there were many in the early 1960s who would have agreed with him. In the wake of the Vassall revelations, The Mirror tabloid newspaper lambasted the inability of the Admiralty and MI5 to detect the gay men in their midst and ran a story - ‘How to spot a possible homo’ - featuring a photograph of a semi-naked Vassall.

It was into this context that the film of From Russia With Love was released. Perhaps this is why, certainly compared with the book, the honeytrap/blackmail element is forced to take a backseat. Maybe it was too raw? Maybe the censors thought the British public didn’t want to see Bond narrowly avoiding being caught in a Vassall-like quandry?

Two years before From Russia With Love, in 1961, the issue of blackmail had been dealt with head on in a ‘X’ rated film, Victim. Dirk Bogarde starred as a middle class man whose male lover kills himself after being blackmailed. The film was intended to shift public attitudes towards homosexuals, perhaps even generate some sympathy for them. It’s now available on DVD rated ‘PG’, which speaks volumes about shifting attitudes over the last sixty years.

Back in 1963, Bond was being positioned - onscreen by SPECTRE, offscreen by the screenwriters - as another headline-grabbing subject of a sex scandal. Not all of this element survived into the version of the film we know today. In the final scene, there’s a jarring cut just after Bond holds the film reel up to the light and announces to Tatiana “He was right, you know -”. Connery is abruptly cut off with an awkward transition to another angle.

Thanks to some keen detective work from fans, we know the rest of the line was “What a performance!”. Bond’s line itself was an echo of the same line spoken by Red Grant as he taunted Bond in the train compartment. That was also cut. The performance in question was Bond’s and Tatiana’s in the bedroom. We had seen their nocturnal activities being filmed behind a mirror earlier in the film but this is almost forgotten until Grant pulls out a reel of film in the train compartment.

The simple version is the lines that the British censors referred to their report as “sexual innuendo” was considered too much for the British public of 1963. The censors demanded cuts if the producers wanted to release the film with an ‘A’ rather than an ‘X’ certificate, which would have massively reduced the audience.

Innuendo has been integral to the Bond films from the very beginning. Indeed, it remains one of the most cherished ingredients. When it was announced ahead of the release of No Time To Die that “James Bond’s cheeky sexual innuendos are staying in the next film despite push to make him politically correct”, The Sun newspaper took it upon itself to breathe a sigh of relief on behalf of the nation, completely missing the point that innuendos are agents of political correctness. How else can you talk about sex in a way that most people find socially acceptable?

As a child, many of the double meanings went right over my head, as they were intended to. It’s only when I rewatched the early films as an adult that I realised how near the knuckle things sometimes got. From Russia With Love’s “what a performance!” is definitely on the tamer end of the spectrum. But would the same have been the case in 1963? Innuendos only work being of their allusive power - they refer to something else from an apparently unrelated context. An innuendo is a covert reference (like pervert = homosexual) which only those who are ‘in the know’ will understand.

From Russia With Love was released within days of the British Prime Minister stepping down amidst another scandal - between straight people this time, albeit outside the confines of marriage. The Vassall revelations had damaged the government but the ‘Profumo affair’, between the Secretary of State for War and a 19-year-old would-be model, Christine Keeler, was the straw that broke the camel’s back. There were even rumours of a security breach, with a Russian naval attach rumoured to be a third participant, forming what the press called a ‘love triangle. Later, it emerged that MI5 had hoped to use Keeler as the bait for a honeytrap of their own, to snare the naval attaché!

In this morally murky milieu, it is possible that any hint of sexual impropriety in the context of espionage - gay or straight - was too near the knuckle and an apparently innocuous word like “performance” had to be snipped out of From Russia With Love.

There are, of course, queer connotations of the word ‘performance’: we often speak of queer people having to perform a role, rather than them being permitted, or feeling comfortable, being themselves. Queer people sometimes feel compelled to ‘pass’ as a different sexual orientation or gender identity in order to fit in.

Although this was probably not conscious on the part of the filmmakers, Bond having to put on a performance to woo Tatiana provides queer viewers with a way into From Russia With Love. For this part, Bond doesn’t have to try very hard to ‘perform’ the role asked of him. He seems very keen on his latest mission as soon as he’s seen the photo of Tatiana, telling M he’s “not too busy”. Would he have suddenly found his in-tray was piling up had M presented him with a photo of an attractive young man? How strongly would M have had to insist on 007’s loyalty to queen and country if he’d kicked up a fuss? How desperate were MI6 to get hold of a Lektor?

On the other end of the innuendo spectrum (and one that did not go over my head as a child) is the exchange between Bond and Tatiana while Bond is waving his Walther in Tatiana’s face.

As we’ve already noted, when it comes to innuendo, context is everything: he’s standing over her wearing just a towel. She’s lying prone, wearing just a velvet choker around her neck. And just in case we didn’t get it, moments later they’re evaluating the size of her mouth for different purposes.

Get a room you two! Preferably one without Rosa Klebb and a SPECTRE agent filming you from the other side of the mirror.

Although Bond is undeniably ‘into’ Tatiana sexually, it’s evident that, for him at least, the mission is more important than the woman. On the boat he tells her bluntly that it’s “Business first”. And when Grant appears pretending to be Bond’s contact, Bond seems willing to go ahead with the escape plan which will leave Tatiana behind. Grant even poses the question: “What are you after: the girl or the Lektor?” Bond doesn’t reply verbally but answers Grant by putting his gun away, seemingly acquiescing to the importance of the Lektor.

This comes not long after Bond and Tatiana have settled into their new identities as David and Caroline Somerset. The sequence where they become acquainted with their accommodation on the Orient Express gives us an idea of what married life might be like for Bond if he ever settled down. When he does eventually get married in On Her Majesty’s Secret Service, married life does not outlive the first five minutes of the honeymoon. The “two-day honeymoon” is cut short here too, but not quite as abruptly.

But it’s all built on a lie - they are not the Somersets but performing as the Somersets. When Bond presents her with blue negligee it’s accompanied by one of Barry’s best cues, which gives the scene some much-needed innocence when it could have easily come across as sexually predatory. While apparently going through the motions of a groom on his wedding night, Bond is actually doing whatever it takes to keep Tatiana placated for the duration of their ‘honeymoon’.

Bond doesn’t care about Tatiana. Not really. But it’s not too much effort for him to play along for the sake of the mission. And if he gets some gratification along the way, that’s an added bonus.

Lying IS Bond’s business. But something I’ve noticed is the films where he sustains a false identity for a prolonged period usually take place in what we could call ‘liminal spaces’. I explored liminality in detail in my queer re-view of The Living Daylights, which shares a lot of similarities with From Russia With Love. Both films are concerned with border crossings, defections and divided loyalties and the action takes place exclusively in locations with long histories of instability and people in transition. Much of From Russia With Love takes place in Istanbul, formerly known as Byzantium and, before that, Constantinople. For centuries it was a meeting place for different cultures - West meets East. At the height of the Cold War, when From Russia With Love takes place, it was a centre for espionage, connotations which continue into the present day (Bond returns to Istanbul twice on screen, in The World Is Not Enough and Skyfall).

In real-life, Istanbul is one of the most cosmopolitan places on Earth, even welcoming queer visitors despite Turkey as a whole being ranked as one of the least LGBTQ+ tolerant out of the countries that who are members of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

One of the things that appealed most to Fleming when he was preparing to write his next Bond adventure was setting a large chunk of it on the Orient Express. You don’t get a more liminal space than travelling from the ‘exotic’ East back to the West, the characters’ temporarily fluid identities refreezing, reverting back to ‘normal’ as they traversed Europe. In the film, we even get maps overlaid (in adventure serial/Indiana Jones style) so we can keep track of where Bond is on his train journey. All the secrets are revealed as Bond gets closer and closer to home. Agatha Christie does the same thing in 1934 with Hercule Poirot in her Murder on the Orient Express. Fleming and Christie reversed the trajectory taken by Graham Greene two years before in his novel Stamboul Train, where he embroiled his characters (including a doggedly determined lesbian journalist) in more and more intrigue as they traversed from West to East, identities shifting as they went. An enthusiastic reviewer of that book, gay novelist L. P. Hartley, observed that:

A long railway journey is always an adventure in which the rules and habits governing one’s daily life temporarily relax their hold.

It wasn’t just novelists who were exploiting the liminal power of trains either. Hitchcock loved setting spy stories and murder mysteries on trains as well, most notably in The Lady Vanishes (1938) and North By Northwest (1959), the latter of which many credit with shaping the Bond films. Hitchcock was no stranger to the theme of homosexuality, although he couldn’t talk about ‘it’ directly so he used codes. Strangers on a Train (1951) was adapted from a novel by lesbian Patricia Highsmith and is crammed with homosexual subtext, Hitchcock’s way of commenting on the Cold War hysteria which resulted in homosexuals being targeted as security risks in the USA, even more aggressively than they were in his home country, the UK. That film has several train scenes but it’s the very first which sets the plot in motion. The transitory nature of the train journey frees the two male characters from the shackles of conventional morality so they can talk openly about committing a murder apiece on each others’ behalf.

In fiction, trains are loci for socially unacceptable sex and violence. No wonder Fleming was so determined to set so much of the book on the Orient Express even though, as the film’s editor points out, it would have made far more sense for Bond and Tatiana to take the plane.

From Russia With Love climaxes in Venice, another liminal space which Bond can’t keep away from (Moonraker, Casino Royale). Venice of course, like Istanbul, was a meeting place for different cultures for centuries and was also a by-word for sexual permissiveness in Shakespeare’s time and, more recently, a code word used by author Daphne du Maurier to describe her same-sex attraction.

Venice, Istanbul, a trans-European train… living a lie is easier in places where people are coming and going and the usual rules may not apply.

Even so, Bond still needs to be careful. From Russia With Love features a repeated use of a recognition code. It’s first initiated by Bond to establish contact with his chauffeur when he arrives in Istanbul, turns out to be Kerim Bey’s son.

Spies use recognition codes to establish who they can and can’t trust. But they’re not alone: throughout history, queer people have used recognition codes to identify people who are like them. It still happens today of course: in a heteronormative world, most people are presumed to be straight and cisgendered and it’s not as if queer people go around with neon signs around their heads. Even a rainbow badge might indicate they’re an ally and not queer themselves. In countries where homosexuality is still illegal, and even in ‘progressive’ countries where being open is not always socially acceptable, codes continue to proliferate.

In addition to words, codes which can put you on someone’s ‘gaydar’ can include certain colours of clothing, a handkerchief in the back pocket, hand gestures and even the right look. Of course, you only want to be detected by the people who are like you - which means you both need to know the recognition code.

A study of how eye-gaze is used by gay people to identify each other observed that:

Gay men and lesbians habitually enact behavior that displays involvement in a shared system of meaning in order to be recognized as members of the gay and lesbian community.

There’s every chance that people who don’t share your sexual orientation will pick up on the shared codes used by a community. Although many now consider it to have died out because it’s no longer required by queer people in Britain, some vocabulary from Polari, the language of gay men, seeped into everyday vernacular. This was in part because the words were heard in mainstream BBC radio broadcasts of the 1960s by queer comedy performers like Kenneth Williams. While this undoubtedly “spoiled the secret”, it was a way of talking about something that was socially taboo in a coded, socially acceptable way, similar to innuendo.

If everyone knows a secret it’s no longer a secret. And in From Russia With Love, everyone seems to know the secret coded exchange involving cigarettes, lighters and matches. Bond uses it again at Belgrade station to establish that another of Bey’s sons, is trustworthy. Bond is unaware that Grant is above him listening to the exchange. At Zagreb station, Grant uses the recognition code to pose as Bond so he can take over Nash’s identity and get close to 007. When Grant unmasks himself as Bond’s adversary he reveals that the recognition code had been sweated out of “one of your men in Tokyo”, meaning he didn’t even need to overhear Bond to acquire the code.

And the British government were concerned that homosexuals were the biggest security risk!

Having said that, there is something very queer about the scene where Grant ‘recognises’ Nash on the station platform. We don’t need to overhear the recognition code - seeing Grant’s lips move is enough. And seeing Grant put on his leather gloves tells us that Nash is not long for this world. For reasons that are never clear, Grant somehow persaudes Nash to go with him to the men’s room. A men’s room affords a certain amount of privacy. It would allow two spies to have a conversation away from prying eyes and ears. It would also allow them to do something else.

Prior to partial legalisation of homosexuality in the England, gay and bisexual men often had no alternative but to seek out other men in toilets, what became knows as ‘cottages’, for sex. And the Bond films can’t keep away from toilets. In particular, see The Living Daylights, GoldenEye and Casino Royale. The queerness in From Russia With Love is further heightened by the exchange being all about lighting another man’s fag (as in British slang for cigarette, although ‘fag’ meaning faggot is etymologically related). “Can I borrow a match?” sounds like a dodgy chat up line in any context, but when the two speakers make an abrupt turn to the right and head directly to the nearest water closet it sounds like they’ll be giving each other much more than ‘a light’.

According to editor Peter Hunt, even the man who played Nash, who was actually the film’s production manager Bill Hill, thought the scene was “preposterous if you thought about it. Here I am arriving in Zagreb station on this terribly important mission to assist a fellow agent and, after we trade the recognition signal, we’re on the way to the bathroom. What were we supposed to be saying anyway: ‘let’s have a pee and then we’ll board the train?’”

Whatever Grant said to Captain Nash to get him into the bathroom, the poor Captain ends up with far more than he bargained for, and his killer’s impersonation of him is wholly accepted by Bond because he can recite the recognition code and he carries the same standard-issue briefcase (another code, but this time based on appearance).

Bond’s unmasking of Grant is probably the most celebrated instance of Bond’s snobbery saving the day. Although Bond’s suspicions of Grant are aroused by constantly referring to him as “old man” and him slipping Chloral Hydrate (the same drug used by Kara in The Living Daylights) into Tatiana’s wine, he professes to Grant that it was his pairing of red wine with fish that gave him away.

Fussy in the extreme.

As Simon Winder remarks: “far from being a merciless killer, at times Bond’s hands seem to flap around in a wilderness of fuss.”

Once again, Bond’s stereotypical gay man traits (and/or those of his upper-class creator, Ian Fleming) come to the fore. His urbanity also comes across as parodically cruel at times, especially towards minor villains. This reaches its apotheosis when he ‘helps’ the truck driver they’ve taken hostage off the boat, which is speeding away from the dock: “Oop, mind the step!” he says, before throwing him over the edge.

As paradoxical as it sounds, From Russia With Love is, at heart, a serious story about a British spy being pimped out by his country. This was an inherently taboo proposition for a 1963 cinema audience. Even though the spy is ostensibly straight and wooing a beautiful woman, it would probably have been uncomfortably close to some of the headline-making sex scandals of the time.

Sex of any description was a hot topic, but still hard to describe openly without resorting to code. But things were starting to shift.

From the relatively safe distance of a few years later, in 1967, the poet Philip Larkin wrote that “sexual intercourse began / in nineteen sixty-three / (which was rather late for me)” and goes on to explain why he settled on that year; because it was “between the end of the “Chatterley” ban / And the Beatles’ first LP”. D.H. Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover was finally published uncensored in November 1960 and The Beatles released Please, Please Me six months before From Russia With Love. Both were cultural milestones which changed their respective landscapes - literature and music - and had wider social repercussions. Sitting between the two, 1962’s Dr. No arguably did the same thing for cinema.

But what about From Russia With Love? There must have been a point where the filmmakers debated whether they should place it safe and ape Dr No’s success or go for it and push the sexual envelope. This was only the second Bond film so the template was not yet securely in place.

In the end, the filmmakers had to work overtime to sublimate the more explicitly sexual elements to make them acceptable, often using innuendo and other codes. In their own retrospective of the 1960s as a whole, the censors at the British Board of Film Classification (BBFC) observe that the ‘swinging Sixties’ were only just starting to swing at the time of the film’s release:

Attitiudes to sexuality were on the change in the wake of the 1957 Wolfenden Report, which recommended a relaxation of the laws concerning homosexuality, although no new legislation was to appear for another ten years.

It’s interesting that the BBFC flag up the importance of the Wolfenden Report, suggesting that it had an impact on more than just gay men but sexual attitudes more widely. Of course, it’s reductive to pinpoint the Wolfenden Report as having this much of an impact by itself. In addition to the cultural milestones and the Profumo and Vassall scandals, the first years of the 1960s also saw the introduction of something many at the time considered scandalous: the first contraceptive pill. Although it was available on the NHS to married women only in 1961, it didn’t become accessible for all until 1967 (that year again!).

Sexual attitudes don’t change overnight. They diffuse through different parts of society at different rates. Caught between the 1957 publication of the Wolfenden Report and the much delayed enactment of its recommendations in 1967, From Russia With Love encapsulates the repressive, heteronormative values of the first half of the 20th Century while also giving audiences, straight or queer, a flavour of greater freedoms to come.

Friends of 00-Dorothy: 007’s Allies

“Once, when I was with M in Tokyo, we had an interesting experience.” Presumably this experience did not involve sweating recognition codes out of people (by whatever means!), which, according to Grant, is what SPECTRE seem to be spending most of their time doing in Japan (although Blofeld’s volcano base must be under construction by this point surely?).

This line of Bond’s suggests that he and M have a relationship outside of business hours. Maybe they even went to an onsen together while in Tokyo? M seems to think Bond is physically up for the Russia job. But does he know for sure? He could have got 007’s vital statistics from his personnel file but I’d like to think the head of the Secret Service wouldn’t gamble his entire organisation’s reputation on an agent’s ability to look drop-dead gorgeous to a Russian defector without checking over the goods himself first. That’s pretty much what Rosa Klebb does with Tatiana. Admittedly, Klebb takes a personal interest in her inspection, but even so, M should make sure Bond comes up to expectations “in the flesh”. Purely professionally of course.

In the novel, M is concerned that Bond might still be in a long-term monogamous relationship so he probes Bond about this before outlining the nature of the mission which, as Bond himself describes it shortly afterwards, amounts to ‘pimping for England’. There are no such concerns in the film. Although it would be an exaggeration to call “old case” Sylvia Trench Bond’s partner (see Girls, below), the fact that we see Bond in some form of on-off relationship before he heads off to woo another woman perhaps indicates a loosening up of social attitudes in the six years between the publication of the novel and the release of the film.

Having allegedly tried “everything else”, Moneypenny implores Bond to take her to Istanbul (which is not, presumably, a euphemism).

The first time Desmond Llewellyn appears as Q he’s all about concealing things. And let’s not forget the brilliantly camp exploding ‘talcum powder’. Nothing is as it seems.

Kerim Bey is less concerned with keeping secrets. He operates in the open and his approach seems to be meeting with success. In the book Bond observes why: 'The public agent often does better than the man who has to spend a lot of time and energy keeping under cover.' I can’t think of a better metaphor for queer people who have to waste time and energy staying ‘under cover’.

Certainly the most fertile of Bond’s ‘daddy’ figures, Kerim doesn’t even keep up a pretence of being in a relationship with one person. He lives, cheerfully, with his sons, who all work for him (“my whole life has been a crusade for larger families”) and his significantly younger mistress, whose libido outpaces even his (“Back to the salt mines!”). A man of large appetites of all descriptions, he grew up in the circus breaking chains with his teeth and bending bars. He’s immediately close with Bond and the affection feels genuine (“How can a friend be in debt?”) so when he is killed (the sacrificial role more commonly filled by the secondary girl) Bond’s anger is white hot. To my knowledge, no one has yet written any slash fiction featuring Bond and Kerim Bey although I’d say it’s only a matter of time.

On the an infamously ‘banned’ laserdisc commentary from 1991, director Terence Young told the story of when he first met actor Pedro Armendariz, for whom he had great affection. Young had accidentally dyed his hair red in the shower with his wife’s rinse and. In trying to correct it at a barber’s he ended up with a green tint. That same day he went to meet Armendariz and felt complelled to tell him “I’m not a fag”, reassuring him that his intentions were strictly professional, green hair being quintessentially gay (apparently). Oh how fragile some men’s masculinity is!

Shady characters: Villains

A misfit in so many ways, despite his fairly conventional appearance, Donald ‘Red’ Grant is one of the queerest villains in the Bond villain pantheon.

His portrayal in the film is more grounded compared with that of the book, where Fleming has Grant’s homicidal urges tied to the lunar cycle. He is literally a lunatic. He gets ‘The Feelings’ once a month and can only sate them by murdering something. I used to think moon-inspired madness was entirely mythical, another case of Fleming using pop science as real science (see also: homosexuals not being able to whistle). I was therefore surprised to find some reasonably reliable and recent research findings which show a tenuous connection between the phases of the moon with murderous actions!

Even so, the filmmakers thought this was too operatic for the onscreen version played by Robert Shaw. They also tone down Fleming’s sexualisation of the character.

Grant begins the book naked. Like, totally naked. And just to assuage any ambiguity, the first three words of Fleming’s text are “The naked man…” When I first read this as a teenager I knew things were off to a good start. It’s Fleming’s most lingering description of the male form in any of his books. And. It. Is. Hot. Quite literally: Grant is dripping with sweat. He’s sopping wet even before a topless girl appears to rub oil all over him. Just in case things are getting a bit too homoerotic, Fleming switches to this heterosexual woman’s point of view, so it’s her who soaks up the sight of the “finest body she’d ever seen” with its “bulging muscles” and “huge biceps”, although this is after the narrator/Fleming has already tempted us with Grant’s tantalising “ridge of fine hairs above his coccyx” (you read that correctly. I typed it out extra carefully).

In the film, both the masseuse and Grant get just enough fabric on their bodies to conceal their modesty. Back in the book, he takes off his clothes without hesitation once again in Chapter 10, when Klebb slams her knuckle-duster into his stomach. The two scenes are economically combined in the film. Fleming, on the other hand, takes any opportunity to get Grant undressed. Teenage me was not complaining.

What is unambiguously the same in both the film and the book is Grant’s blondness. He’s the first of the films’ blond villains, male blondness often connoting femininity or he-doth-protest-too-much hypermasculinity in the world of 007 (see You Only Live Twice, For Your Eyes Only, The Living Daylights and Tomorrow Never Dies). Terence Young stipulated that Grant’s blondness was essential to the character and stuck to his guns even when Robert Shaw almost walked away from the role, citing his reluctance to dye his hair. Grant’s blondness might appear to make Grant the antithesis of the dark-haired Bond but in other ways they are unnervingly the same. In the book, the similarities between the characters are made even more abundantly clear by Fleming repeatedly describing his facial features as “cruel”, the same adjective he uses for Bond’s appearance.

Although Grant might bear a passing physical resemblance to Bond, Fleming uses the word ‘queer’ in association with Grant three times, the most of any character in all the books, but only after he boards the Orient Express. The word queer was being increasingly used with a ‘homosexual’ meaning in 1957 and I believe Fleming was using this word to indicate to a portion of his audience that Bond knew something was ‘off’ about Grant. A further detail which might be an allusion to Grant’s unconventional proclivities is that Klebb notes he was “recruited in Tangier”, which was a haven for gay men in the 1950s and 1960s. It’s a location that reoccurs with queer assocations in Bond (see The Living Daylights, Spectre).

Bond is complimentary about Grant’s physique. Connery’s delivery of the line “You look very fit Nash” always sounds to me like it’s not just full of admiration but imbued with a little jealousy. Or is it Bond’s scepticism that a low level MI6 operative would be so hench?

And is it Bond’s admiration/jealousy or Connery’s? Connery had been a body builder himself but Robert Shaw spent 5-6 hours in the gym every day to prepare for his role as Grant. To quote the Village People: “every man wants to be a macho macho man / to have the kind of body, always in demand”.

The queerest scene of Grant’s comes just prior to the big fight, when he has Bond on his knees in front of him. It’s a sexualised power trip, a reversal of the same situation from earlier, where Bond was the one in charge, standing over Tatiana with his gun in hand. Grant acknowledges he’s getting “a kick” out of taunting Bond and explaining to him how things are going to go down: “You may know the right wines but you’re the one on your knees.” He tells Bond how he will die: “It’ll be slow and painful… The first one won’t kill you. Nor the second. Not even the third. Not till you crawl over here and you kiss my foot.” 26 years later, Sanchez delivers a similar speech in Licence To Kill, although Sanchez invites Bond to “kiss my ass” instead, just in case we didn’t catch the homoeroticism.

The celebrated fight in the tightly-packed railway compartment (edited to perfection by Peter Hunt) operates as a release of this homoerotic energy. As established right from the pre-titles sequence, Grant’s preferred method of killing is to garrotte the unfortunate victim, which is about as intimate as you can get, so we know he will want to get close to Bond. Who knows who - or what - Grant is into in the bedroom. His leather gloves may hint at a particular kink. I’m not going to judge! But there is an uncomfortably pleasurable dimension to Grant’s acts of violence, in both the film and the book, most clearly shown when he’s grappling with Bond on the train.

In both versions, Bond defeats Grant by turning his own ‘weapon’ against him, something we see time and time again in the Bond films, and it always carries a Freudian undercurrent. In the book it’s Grant’s gun, disguised as a book. Grant has Bond “half on his back”, is digging his fingers into Bond’s thigh and leaning over to bite him, like a vampire. It’s at this point that Fleming tells us that “Bond's scrabbling fingers felt something hard. The book!”

In the film, Bond uses the piano wire inside Grant’s watch to asphyxiate Grant. It’s a thoroughly cathartic kill and the filmmakers allow us to see Bond as he steadily recovers, slowly, from their tussling. It’s unusual, even at this early stage in the series, to see Bond so exhausted after a fight. The camera lingers on his face almost post-coitally, leaving us in no doubt that Grant definitely put him through a work out.

Although we should be careful about reading into an author’s own views based on their works, I think it’s safe to say that Ian Fleming was not a fan of lesbians.

Rosa Klebb is one of the few explicitly queer villains in the Bond series. I say explicitly but she doesn’t actually say she’s a lesbian. Nevertheless, she touches up Tatiana’s knee. If it’s a code then you don’t need a Lektor to decipher it. It’s a clear indicator in anyone’s book.

Actually, in the book, Fleming doesn’t use the word lesbian either. In Chapter 7 he has Kronsteen surmise that Klebb is the “rarest of all sexual types”, a “neuter”. There are “stories of men and, yes, of women” and, Kronsteen decides “she might enjoy the act physically, but the instrument was of no importance. For her, sex was nothing more than an itch.” So: Asexual? Bisexual? Aromantic?

A couple of chapters later, Klebb finishes her interview with Tatiana (reproduced faithfully in most other regards in the film) by changing into a “semi-transparent nightgown in orange crèpe de chine”. Tatiana runs from the room. I suppose that answers, for Tatiana, the question I posed about Bond: if you had to sleep with someone you didn’t find attractive to aid your country, would you do it? In Tatiana’s case it’s a definite NO, at least when that someone is the repugnant Rosa Klebb.

The two moments most people remember in association with Klebb are violent actions towards men: her punching of Grant in the abdomen with a knuckle-duster and her attempt to kill Bond with her poison-tipped shoes. Are we intended to view these as the actions of stereotypical ‘man-hating lesbian’ or just a professional doing their job?

In Goldfinger, Fleming famously had Bond pity male and female homosexuals. Who knows what Fleming’s gay male friends - Noel Coward, Cecil Beaton, Somerset Maugham - thought about this. Patronising much? In the same novel he posits that all a lesbian needs is the right man (said man being James Bond). And in private correspondence to a fan he called lesbianism a “psychological malady”. While I would never attempt to apologise on behalf of anyone who held such spectacularly ignorant views, let’s remember that homosexuality was not declassified as a mental illness by the World Health Organisation until 1990. Ian Fleming may have been ignorant but he was hardly in a minority.

Even so, the novel and film of From Russia With Love are not exactly odes to Sappho.

Editor Peter Hunt, a gay man, had no hesitation in labelling Klebb as lesbian when he was interviewed for that infamous laserdisc commentary in 1991 and thought the same sex attraction was presented in “extremely good taste”. On the same commentary, writer Richard Maibaum was marginally less committal about the “lesbianism”, but credited Terence Young with the character’s portrayal, her attraction to Tatiana being the “only redeeming feature” who was otherwise completely odious in the screenplay.

What possibly made the character so reprehensible in the original audience’s eyes is a significant change from the novel: The film’s Klebb is a defector, from the KGB to SPECTRE, which places her in the same untrustworthy category as real-life defectors Burgess and Maclean. She can’t even be trusted to do evil in the name of Mother Russia. She has sold out. Of course, this significant shift from the book is entirely a result of the filmmakers being mindful of posterity, envisioning a post-Cold War period when James Bond films could be marketed to Communists. (In fact, Terence Young maintained that Soviet General Secretary Leonid Brezhnev himself loved the film, even at the time, having borrowed a copy from the British Embassy in Moscow.) But the act of defection, as I have explored with The Living Daylights, can mean more than just someone switching allegiance to another nation. Research has shown that homosexuals are often being viewed as ‘traitors’ to heterosexual society because they are perceived as having switched sexual orientation and turned their backs on the herd.

Klebb was played by actress Lotte Lenya, a sex symbol in the early stages of her career when she also became the muse of songwriting legend Kurt Weill. According to the director, again on that infamous ‘banned’ commentary track, Lenya was “screwing” everyone. Whether Lenya was really that amorous or whether Young is applying a double-standard (by all reports the male stars were hardly the epitome of monogamy on the Bond productions) is unclear, and none of our business really. But the fact is Lenya, although in her early sixties (and therefore, in film-making terms, ancient - that double standard again), was an attractive woman who excited admiration. The filmmakers had to go to some effort - with costuming, make-up and hair - to make her look unattractive. Had the character been straight, it’s not hard to imagine that Lenya could have just as easily been played Klebb as an attractive femme fatale.

Like Wint and Kidd she’s deeply problematic as a queer representation. But like those male homosexuals, at least she’s a representation. As I explored with Diamonds Are Forever, sometimes that might be better than nothing at all.

For some, just the fact that she is a woman in a position of authority who causes her male colleagues to tremble (particularly in the book) makes her something of a role model. In the film, prior to joining SPECTRE she was head of Operations for SMERSH, in charge of bringing death to spies. And in the book, she succeeds in doing what so many men have failed to do and she does it with surprising efficiency: she kills James Bond! (Fleming only brought him back to life when fellow novelist Raymond Chandler convinced him to).

Whenever I watched From Russia With Love as a child I always found something queer about Kronsteen. SPECTRE’s DIrector of Planning is excessively well-mannered, cool and collected, even when orchestrating the death and dishonour of 007. The way he lights his cigarettes shows he has some of Bond’s fussiness. But unlike Bond he doesn’t make a big song and dance about his personal preferences. And although I’ve always been rubbish at chess, I could relate to a man who liked quiet hobbies. You can’t imagine Kronsteen kicking a ball around in the back garden, at any age. I cringe that even as a kid I was falling prey to thinking of gay men in such stereotypical ways, but I appreciated above all that he was so self-controlled. He even dies gracefully. He was memorably played by Czechoslovakian actor Vladek Sheybal, whose later roles included a gay sculptor and a gay vampire. Perhaps sensing that he couldn’t have all of Bond’s adversaries be so queer (Grant, Klebb AND Kronsteen!), Fleming gives him a wife in the novel.

Blofeld makes his first appearance - of sorts. He doesn’t appear in the book at all, where SPECTRE doesn’t get a look in: the novel’s villains are unequivocally working for the Soviet Union.

Of all the villains, Blofeld’s identity is the hardest to pin down, and not just because we don’t see his face until You Only Live Twice. In From Russia With Love he does have hair, leading us to believe he’s either wearing a wig here or, four years down the line, he will be suffering from an extreme case of alopecia.

In terms of Blofeld’s sexual orientation it’s anyone’s guess and very reliant on the actor portraying him and the lines he is given: in On Her Majesty’s Secret Service, Telly Savalas is urbane and seems to take a romantic interest in Tracy; whereas in Diamonds Are Forever, Charles Gray is waspishly camp and resplendent in drag. And in Spectre… what is really driving Blofeld’s animosity towards his little adopted brother? That’s a whole lifetime-of-therapy conundrum right there.

Even in the books, Fleming seems unsure at times, making him unambiguously asexual in Thunderball and then hedging a little in the two follow-ups.

How much should we make of his white Persian cat? Blofeld’s cat (an invention for the films) became THE must-have villain accessory in homages such as Austin Powers and Inspector Gadget (where the villain’s face is also concealed). But why do cats so rarely appear as male companions in films and media which play it ‘straight’?

Since at least the 19th Century, cats have carried feminine connotations in most Western cultures, usually in contrast with ‘man’s best friend’: dogs. As with all gender stereotypes, this is all learned behaviour and utterly ridiculous if you subject it to any serious scrutiny. This gender imbalance is not universal and in From Russia With Love’s main location, Istanbul, cats are considered the ‘soul of the city’, beloved by everyone (although it must be said that ‘gay men of Istanbul with cats’ is totally a thing).

Protesting about stereotyping is one of my favourite pastimes (a close second behind looking at photos of attractive men with cats). And while we can continue to protest until the cat comes home, what must the reality have been for audiences in 1963? A single man living on his boat with a snow-white pedigree Persian pussy to whom he feeds Siamese fighting fish? I’m willing to bet it raised a few eyebrows.

You go gurls!

From Russia With Love has more than its fair share of girl-on-girl action. Although shot with a straight male gaze (and edited by a gay man), I imagine much of it works just as well for some queer women in the audience.

The fight of the gypsy girls did, by all accounts, pose the most problems with the censors. Even though Peter Hunt was not averse to taking the censor out for a multiple-Martini lunch to soften him up before heading back into the editing room for the afternoon, he still had a battle on his hands. At one point the censor claimed he could see pubic hair on one of the girls, similar to the way we imagine we see a knife slice into Janet Leigh’s body in Psycho. We don’t. And there is no pubic hair on display in this film. But sometimes clever editing allows our imagination to fill in the blanks.

By the standards of 1963, it’s a very sexualised scene, although it pales next to the book version which reads like pornography, and not the softcore variety. At one point, one of the girls bites the others breasts, drawing blood. The fight is structured like a striptease, over three colourfully-described pages, with all of the clothes falling off by the end (it’s Chapter 18 if you want to check for, you know, research purposes).

A 2015 study by Lucinda Brown cited the 2003 Madonna/Britney Spears kiss at the MTV Awards as being a watershed moment that led to a proliferation of straight women feeling pressured into same-sex public behaviour to garner the attention of straight men. Rightly or wrongly, the film of From Russia With Love was doing it fifty years earlier.

Although in the film it is implied, visually, that Bond did choose a winner of the fight (the Zora character is standing in closer proximity to the chief and his son as Bond departs), it’s clear the filmmakers were not interested in the outcome and assumed most of the audience wouldn’t either. In many viewers’ minds the real winner is Bond and it has doubtless fuelled many fantasies of not just straight men but also gay and bisexual women.

The main girl-on-girl event only appears in the film, not the book, and is not sexualised. That is, unless you see it as a battle for the body of Tatiana Romanova and not her mind. It’s debatable.

I speak, of course, about Tatiana’s climactic showdown with Rosa Klebb. This is arguably the core drama of the film. We don’t doubt that Bond’s sexual magnetism will see him through the main part of the mission. The question at the heart of the film is: whose side is Tatiana really on? Will her love for Bond overwhelm her love of country? Tatiana still thinks Klebb is working for Mother Russia when Klebb infiltrates their Venice hotel room. The climax hinges on whether she will come back to save James, throwing off Klebb’s aim. And then, so rare in a Bond film, the girl gets to fire the fatal shot that kills the villain! Brava Tatiana!

Tatiana chooses her bed and now must lie in it - Bond’s rather than Klebb’s.

For Fleming, it was enough for Tatiana to hook up with James romantically. By giving her the surname of the pre-revolution Russian royal family (to whom she is distantly related) he drops a massive hint that she will turn, something the book’s Kronseteen is wary of but Klebb dismisses. Perhaps Klebb is blinded by love?

Both the book and the film make a point of Tatiana not being a virgin during a period when sex outside of ‘wedlock’ was still generally frowned up in 1963. When she and Bond play at being a “respectable English couple” honeymooning on the Orient Express, is Tatiana really in love with Bond, in love with the idea of being in love or desperate (understandably!) for some assurance that she will be taken care of now she has turned her back on everything she knows?

Although we know they’ve had sex in the Istanbual hotel room, the film plays it a little more coyly than the original screenplay once they get to the train, where Bond and Tatiania are depicted in bed together right after Bond gives her the negligee, their feet poking out. In the finished film, Bond is fully clothed. They definitely have sex again a couple of scenes later following a discussion about what is and isn’t “kulturny” (socially acceptable) at 4 o’clock in the afternoon. In the script Bond pulled down the window blind to sell the idea that they wouldn’t be heading down to the dining car anytime soon, but Peter Hunt chose to cut to a shot of the train’s coupling rod pounding up and down. Much more subtle!

Is Tatiana a realistic applicant for the role of Bond’s long-term partner? When he tells her that it’s customary in England for women to do what their husbands tell them to do she tells him that “there are some English customs that are going to change”. Unless one of those rules is monogamy, we know Bond is unlikely to be seeing Tatiana again after the mission is complete. She even has to symbolically give back the “government property” wedding ring before they’ve even left Venice!

A more likely prospect for some kind of relationship is Sylvia Trench, returning from Dr. No, a character who seemingly makes her own rules and, like Bond, isn’t precious about staying monogamous. Even so, the filmmakers gave up attempting to attach even these loose strings to Bond after From Russia With Love. But according to actress Eunice Gayson herself, she was originally scheduled to return in Goldfinger, opening up the possibility that we might have seen Bond in a polyamorous relationship or at least a ‘friend with benefits’. For reasons that were never clear, the plan changed when Terence Young left the project and Guy Hamilton took over as director. Are we to infer, therefore, that Bond grew tired of her? It’s more likely to be the other way around, with Trench getting fed up with Bond gallivanting off and leaving when things are just getting interesting.

When Ian Fleming was interviewed for BBC Radio 4’s Desert Island Discs, only a couple of months ahead of From Russia With Love’s cinema release, he remarked that writing a new Bond book every year gave him the opportunity to give Bond one girl per year. He followed this up, a tad defensively, with: “I don’t see anything wrong with that”. Fleming was treading a fine line: on the one hand, he didn’t want to offend more traditional listeners/readers/viewers by having Bond sleep with more than one woman at a time. On the other, he wanted to inject his stories with the excitement of new conquests. Fleming himself was married but hardly monogamous. This was reality for Bond’s creator. But in censorious 1963, for many Bond fans, it was purely a fantasy. At least between the covers of a Bond novel, they could live this fantasy vicariously.

Camp (as Dr. Christmas Jones)

On the set of From Russia With Love, Fleming told director Terence Young that his films were a lot funnier than the books he’d written. If only he’d lived to see how Moonraker was ‘adapted’ from his novel! Generally thought of as one of the least campy Bond films, From Russia With Love has a few stand-out elements that show the filmmakers were not always taking things seriously.

SPECTRE have a predilection for black leather. Their helicopter pilots look like they’ve just escaped from (or on their way to) a Tom of Finland exhibition. Walter Gotell’s character, Morzeny, exhibits a similar taste too (in contrast with his appearance as the head of the KGB, 14 years later in The Spy Who Loved Me).

I’ve never cared much for the straight-laced title song but I love the histrionic instrumental version (the brass sounds like machine guns!) over the opening titles with the credits projected onto belly dancers. A ripped male torso or two would make it even better, but this was 1963 after all.

Kerim Bey’s periscope is a sublimely silly plot contrivance that is basically an excuse to show off a nice pair of legs (they’re not actress Daniela Bianchi’s - a leg model was cast just for this scene). The sequence where Bond and Bey ogle a pretty pair of pins always leaves me feeling like I’ve watched a scene from farcical Cary Grant/Tony Curtis starrer Operation Petticoat rather than another 1959 submarine film, Up Periscope, which, despite having a filthy-sounding title, is actually boringly straight-laced.

With SPECTRE’s training camp the clue is in the name. It has been widely parodied but the original is wildly silly - but also cool. As Mike Myers declares in Wayne’s World (a few years before spoofing Bond at large with Austin Powers): “I just always wanted to open a door to a bunch of people who are getting trained like in James Bond movies.”

I’ve explored Blofeld’s ring before. Don’t go there! Instead, head to You Only Live Twice for a detailed discussion of its queer significance. In Blofeld’s first appearance they are even more prominent, perhaps compensating for us not being able to see his face.

For my money, this film’s conspicuously hot Bond boy with a bit part is Kerim’s son Mahmet, played by actor Nushet Ataer, who meets Bond at Belgrade station. He’s a Turkish delight!

Queer verdict: 005 (out of a possible 007)

While all films reflect the period in which they were released, has ever a Bond movie been so keyed into its time? Being made on the cusp of the sexual revolution means that, although From Russia With Love positively teems with transgressive sexuality of most varieties, it might not seem initially to be that subversive. But you don’t need a Lektor to crack its codes - just rewatch it with queer eyes.

Acknowledgements/further reading

I found the resources on the UK National Archives website invaluable for this piece, particularly their podcasts, many of which unearth hitherto hidden or hard to find LGBTQ+ history. Mark Dunton’s on ‘The Scandalous Case of John Vassall’ is a brilliant feat of scholarship and storytelling - very entertaining. I only knew the barest outline of the Vassall case before and this more than filled in the blanks.

The ‘banned’ laserdisc commentary for From Russia With Love, featuring Terence Young, Peter Hunt and Richard Maibaum, is available on 007 Dossier and is a treasure trove of political incorrectness and candid behind the scenes insights. No wonder it was so quickly removed from sale!

Thank you to everyone on Twitter who shared their views and for their allyship, in particular @notperfectedyet for his unflagging support and his insight into the outcome of the gyspy girl fight and @backlotte for her thoughts on Klebb.